studio 1000

Diese Reihe eignet sich ideal für Sprachanfänger, die über einen kleinen Wortschatz verfügen. Lediglich die 1000 häufigsten Wörter der jeweiligen Lektüresprache werden als bekannt vorausgesetzt, die zudem als Wortlisten im PDF-Format zum Download bereitstehen. Im Gegensatz zu anderen Textausgaben für Sprachanfänger wurden diese Texte nicht vereinfacht, sondern orientieren sich grundsätzlich am Original. Darum sei diese Reihe auch fortgeschritteneren Leserinnen und Lesern ans Herz gelegt, da sich in allen historischen Texten stets auch Wörter, abweichende Schreibungen, Idiome u.ä. vorfinden, die in der heutigen Verkehrssprache wenig oder gar nicht gebräuchlich sind.

In dieser Reihe sind für Englisch bereits erschienen:

- Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

- Robert Louis Stevenson, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

- Oscar Wilde, The Canterville Ghost, The Happy Prince and Other Tales

Die 1000 wichtigsten Wörter Englisch – PDF

studio 3000

An fortgeschrittenere Leserinnen und Leser richtet sich die Reihe studio 3000, in der immerhin die ca. 3000 häufigsten Wörter der jeweiligen Lektüresprache vorausgesetzt werden. Zugrunde gelegt wird die Auswahl des recht populären „Langenscheidt Vokabeltrainer Englisch“. Spätestens nach vier bis sechs Jahren Unterricht in einer allgemeinbildenden Schule wird dieser Wortschatz normalerweise sicher beherrscht.

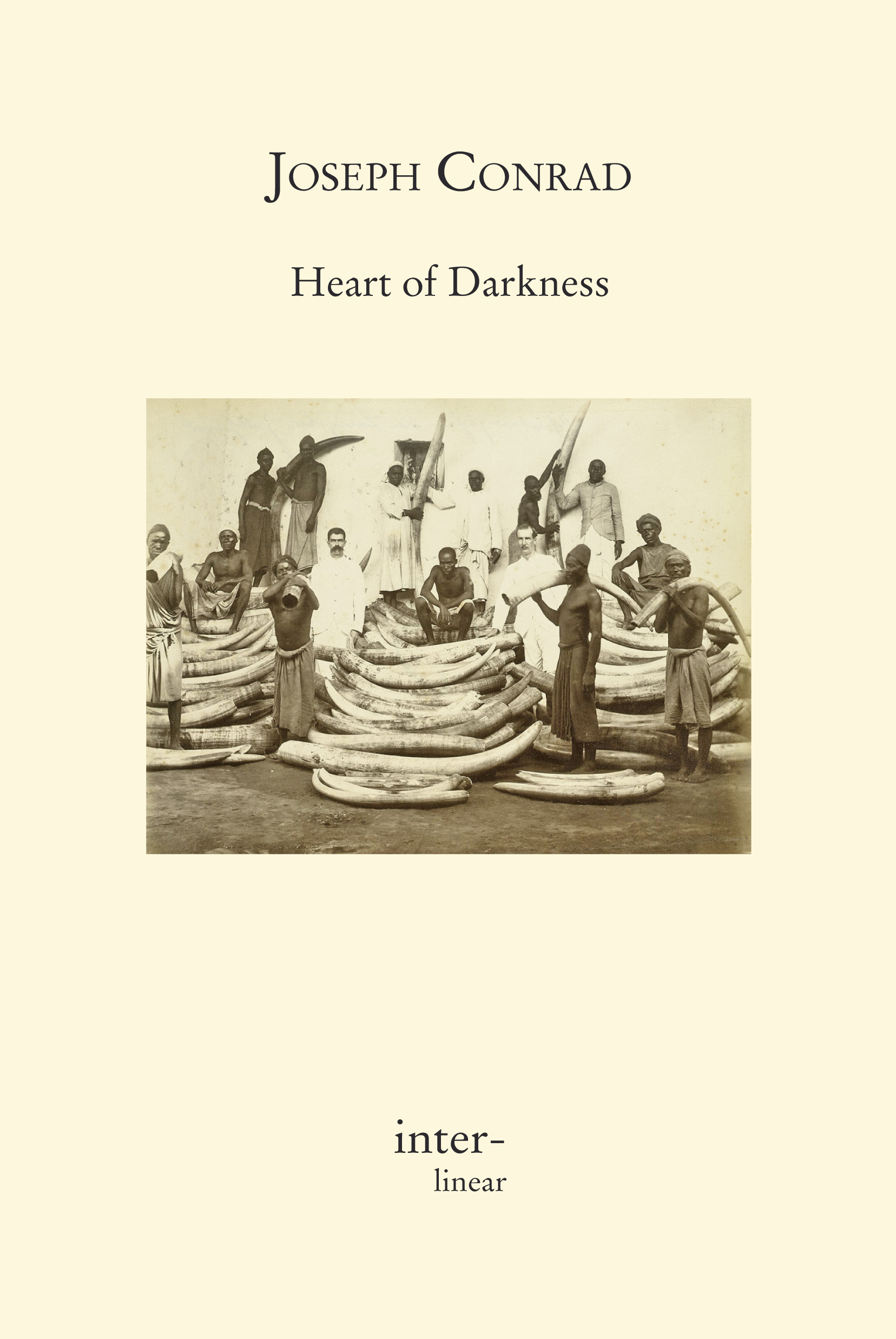

In dieser Reihe sind für Englisch bereits erschienen:

- Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

- James Joyce, Dubliners

- Katherine Mansfield, Bliss and Other Stories

- Katherine Mansfield, The Garden Party and Other Stories

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Raven and Other Poems

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Fall of the House of Usher and Other Tales

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Murders in the Rue Morgue and The Purloined Letter

- Jonathan Swift, A Voyage to Lilliput - First Part of Gulliver’s Travels

Shakespeare

Die Interlinearausgaben der Werke Shakespeares unterscheiden sich in ihrer Anlage von der vorangegangenen Reihe im wesentlichen darin, dass hier der Wortschatz des an Schulen und Hochschulen gebräuchlichen „Grund- und Aufbauwortschatz Englisch“ aus dem Klett-Verlag vorausgesetzt wird. Das gesamte darüber hinausgehende Vokabular wird interlinear vermittelt, so dass umständliches Suchen nach weniger geläufigen oder heute nicht mehr existierenden Ausdrücken unnötig und flüssiges Lesen möglich wird. Sofern das Bedeutungsspektrum eines Worts oder Idioms in unserer Zeit von dem zu Lebzeiten des Autors abweicht, wird in der Regel beides vermittelt. Für das Verständnis wichtige Hintergrundinformationen und Interpretationen schwer verständlicher Stellen erscheinen als Fußnoten auf derselben Seite. Zudem werden schwierigere Passagen interlinear so weit übertragen, dass ein vollständiges Erfassen des Textsinns mühelos möglich ist. So dürfte die Lektüre dieser historischen, dem heutigen Englisch am meisten entgegenstehenden Texte auch für ungeübte Shakespeare-Leser zum Vergnügen werden.

Es sind bereits erschienen:

- William Shakespeare, Macbeth

- William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

- William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

- William Shakespeare, Othello

- William Shakespeare, King Lear

- William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

- William Shakespeare, Hamlet

- William Shakespeare, Sonnets

Alle Texte sind bei Amazon und bis heute nur dort erhältlich.